Ah creative destruction, ain’t it grand? We have seen this economic force, championed almost a centruy ago by the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter, chew up dozens if not hundreds of industries and shake up, realign or otherwise wipe out millions of jobs in recent decades.

Ah creative destruction, ain’t it grand? We have seen this economic force, championed almost a centruy ago by the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter, chew up dozens if not hundreds of industries and shake up, realign or otherwise wipe out millions of jobs in recent decades.

The Internet wave and Moore’s Law of computing power have accelerated, broadened and intensified the impact of all this creative destruction. A supercomputer that cost $20 million and occupied an entire room in the 1980s now is outgunned by the $200 smartphone in your pocket. In the U.S. we now have an estimated 425 million Internet-connected devices: more than one for every inhabitant. Worldwide, by 2020 we are expected to hit 12.5 BILLION Net gadgets. Along the way, countless new industries have been born, grown up huge and have withered (RAM chips, fax machines, phone-answering devices, disk drives, CDs, VCRs, DVDs, electronics stores, desktop PCs, laptops…).

But at what point does all this good-for-us, creative destruction turn to the dark side—at what point is it indiscriminate destruction?

A few world-class observers will debate the upsides and downsides of all this on a panel I am moderating early next week at the Milken Global Conference in Beverly Hills: “Adjusting to the Tech Revolution: Surfing the Wave or Swept Away.” (With apologies to Lina Wertmuller.) See the lineup, here: http://bit.ly/1l9Rmde

In the insular world of conferences and wonky panel discussions, the Milken confab may boast the world’s biggest collection of the super-smart, the super-powerful, and the super-rich. It’s smaller than the better-known World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, but much smarter, a whole let less preachy and, horror of horrors!, it is distinctly pro-business. I have most of these gatherings in the past decade-plus; one year, I had my picture taken with four or five Nobel Laureates. Fun guys.

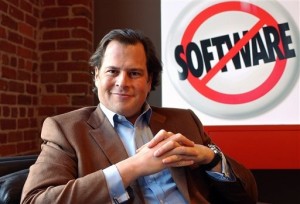

At the panel I’m anchoring next Tuesday, one star will be Marc Benioff, CEO of Salesforce.com. I met him a few months after he founded the company in 1999, and it has been a force for creative destruction in the software industry ever since. Salesforce was a “cloud” software company almost before the buzzword was coined, shaking up the enterprise software market dominated by Oracle, Sybase, Siebel Systems, Peoplesoft, SAP and others. We’ll find out how he hopes to avoid getting crushed by the same wave of creative destruction that he unleashed on the companies that came before his.

Beniof the Destroyer will be joined by a guy on the receiving end of creative destruction: Steve Case, whose America Online acquired Time Warner for $164 billion as the dotcom bubble was bursting in the year 2000. That led to more than $100 billion in writeoffs and the sale or spinoff of most of the biggest pieces of the amalgam, including AOL itself.

Beniof the Destroyer will be joined by a guy on the receiving end of creative destruction: Steve Case, whose America Online acquired Time Warner for $164 billion as the dotcom bubble was bursting in the year 2000. That led to more than $100 billion in writeoffs and the sale or spinoff of most of the biggest pieces of the amalgam, including AOL itself.

Case now runs Revolution, an investment firm that pushes disruptive technologies. You would think Case himself has had enough of that disruptive stuff. And you might wonder howizzit he had any money left to invest at all. Maybe I’ll ask him.

The third and final member of the panel will be an academic, Stanford University fellow and author Vivek Wadhwa.

In tech, engineers do things because they can, and the relentless advance of computing power (doubling every 18 months for the past 40 years) has shortened product life cycles and hastened entire industries toward their saturation points and the tepid, replacement growth rates that are inevitable.

The personal computer arrived in 1980 and pretty much had a strong, 30-year run. Not so for the smartphone, which arrived with the advent of the Apple iPhone in June 2007, only seven years ago.

“The smartphone platform is already over,” as one tech exec told me the other day. The Apple iPhone came out only in June 2007, but now more than a billion people around the world have smartphones, and annual sales now are at a billion units a year.

“The smartphone platform is already over,” as one tech exec told me the other day. The Apple iPhone came out only in June 2007, but now more than a billion people around the world have smartphones, and annual sales now are at a billion units a year.

The tablet market soon may near its own saturation point, just four fast years after Apple unveiled the first iPad. Now some 300 million worldwide are out and about. A total 220 million tablets were sold in 2013, up 54%, IDC says. But in just three years the tablet market will have only single-digit sales growth, the forecaster says, a bigger “phablet” smartphones rise from the bottom up.

Already you can feel the panic in tech firms’ search for the next trillion-dollar platform, as they spend billions on barely existent companies and futuristic tech right out of “Terminator.” See Facebook’s $2 billion buy of Oculus. http://bit.ly/1mH132v

Tech keeps on trucking, advancing forward though I’d bet most of us don’t use 90% of the features and abilities that our gadgets can handle. We obediently upgrade our phones every two years, though the only difference we experience is faster texting.

Meanwhile, we are losing our ability for deep reading and comprehension, as our minds tailor their ability to digest dozens of small bursts of factoids without context. We read three paragraphs on a smartphone screen and feel as though that counts for knowing the full picture. It doesn’t.

And we are lost in our own screens, furiously texting and tweeting and emailing and slicing and dicing and retweeting and liking and commenting. It’s no longer a gender gap or a generation gap, it’s an attention-span gap. It is as if we no longer can bear to be alone to our own thoughts and open to what we see. Or even bear to look into the eyes of another human being. These gadgets that open the entire world to us, they end up blinding us to what’s right in front of us—to the spouse sitting across from you at dinner right now.

Can we all. Just. Slow. The heck. Down?

Um, no, actually, we cannot. There is no slowing down the Internet wave of creative (and at times indiscriminate) destruction. Vivek Wadhwa, who studies these things, says this wave of destruction will accelerate and become even more disruptive in the near future. On the panel next Tuesday, he will talk about how technology’s pace is advancing exponentially, doubling itself continually as new waves arise, including 3D printing, genomics and robots and drones. But the ability of business and government to absorb it and use it is advancing only linearally and all too slowly.

In that gap between the torrid advance of tech and the poky pace of our ability to exploit it, huge amounts of creative and indiscriminate destruction will unfold. So fasten your seatbelts and hold on to your wits and your nerve: This ride is about get even bumpier.