At 11 o’clock this morning the nine Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States are set to hear arguments in a case that could determine whether content remains king—or loses a cornerstone of copyright protection, toppling an economic underpinning of the entire entertainment business.

At 11 o’clock this morning the nine Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States are set to hear arguments in a case that could determine whether content remains king—or loses a cornerstone of copyright protection, toppling an economic underpinning of the entire entertainment business.

The case is American Broadcasting Cos. vs. Aereo Inc. Aereo is the Barry Diller-backed smartphone TV service that has started beaming supposedly “free” broadcast signals of ABC, CBS, NBC and Fox networks and their local stations to subscribers in 11 cities. Aereo does this without paying the broadcasters any cut of the fees it collects.

The networks say this smacks of signal theft, and they are right. Aereo will lose this case, I predict—and it should lose this case.

Aereo’s argument, essentially, is that it can’t steal what is already handed out free of charge: that the networks’ over-the-air broadcast signal, delivered on airwaves granted to them free by the federal government, therefore is free for Aereo to grab out of the sky and resell to its smartphone customers. But it’s the airwaves that are free and publicly owned, not the copyrighted content that travels onboard those airwaves. Entertainment companies produced that content at a cost of billions of dollars.

If the Supremes rule that Aereo doesn’t have to pay for zapping that content to its own subs, why couldn’t cable systems balk at paying $1 billion a year in “retransmission fees” to local stations for the same broadcast shows? Could Aereo extend its antenna scheme to cable networks, too, arguing it is merely porting to smartphones the content that cable subscribers already have paid to receive?

CBS and Fox have said they would turn their over-the-air networks into pay-cable channels if Aereo wins. The NFL has said it would stop airing games on the broadcast nets.

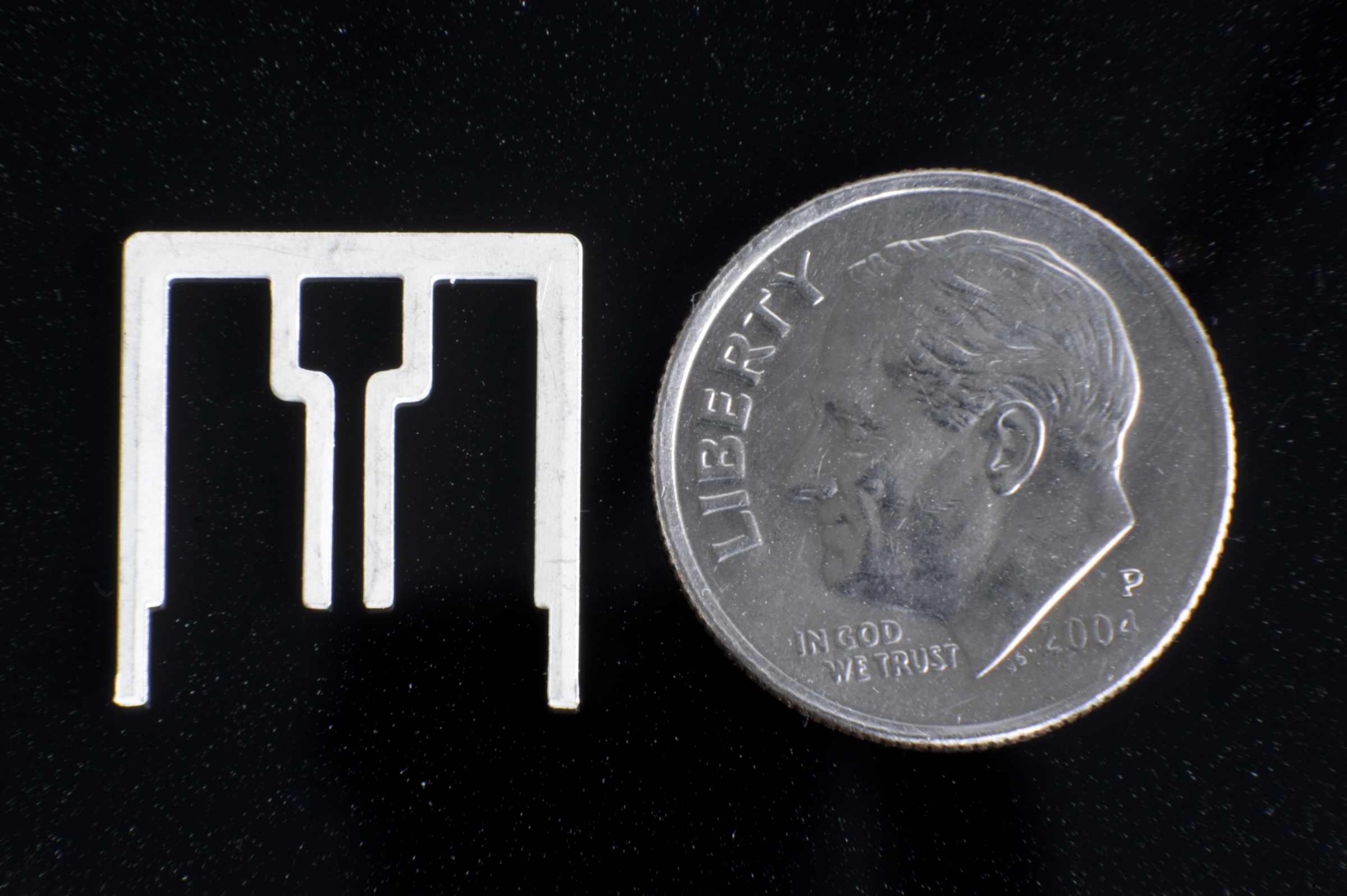

Two federal court rulings had declined to stop the Aereo service pending an outcome in copyright-infringement trials. They were swayed by Aereo’s tiny-antennae scheme: It places thousands of miniature, dime-sized antennae (see photo above), one for each subscriber, in metal cabinets set up in neighborhoods (say, Brooklyn for the New York service, which was the first to light up). It likens these teensy rabbit-ears to the old antennae on rooftops.

Aereo admits it uses this scheme to try to fly below the radar of a federal appeals court ruling several years ago, which allowed Cablevision to store-and-forward online delivery of the programming on its local cable systems. One big difference being that Cablevision paid for every piece of content involved, while Aereo pays for none of it.

A dissenting judge in an appeals court ruling that favored Aereo complained that the teensy-antenna scheme was a “Rube Goldberg-like contrivance, over-engineered in an attempt to avoid the reach of the Copyright Act and take advantage of a perceived loophole in the law.” What he said.

Late last year the U.S. Supreme Court surprised everyone by stepping in to take the case. That may indicate the High Court is worried about the damage the new service could do to intellectual property rights and to the networks’ business, one network lawyer has told me. Another net exec privately predicts that the broadcasters will triumph over Aereo (but lose in their silly lawsuit against Dish Network’s Hopper ad-zapping dvr).

Barry Diller, chairman of IAC Corp., an Aereo investor, is the man who started the fourth broadcast network, Fox Broadcasting, in the 1980s. Now he seeks to disrupt that old business in a way that could devastate it. (Albeit he neglected to mention his Fox role in his op-ed in The Wall Street Journal last week, defending Aereo as innovation: http://on.wsj.com/1po6qrX

The regrettable thing is that Aereo could have gone another way. Rather than play the renegade and pilfer broadcasters’ signals with impunity—without giving them so much as the courtesy of a phone call—Aereo could have partnered with them. It could have offered the networks a great, cheap technology for getting them into smartphones over the Net. Aereo itself was surprised that many customers play the signal from their gadgets on their HDTV screens at home, letting them go “over the top” and watch TV without bowing to the cable guy.

Thus, Aereo could offer broadcasters instant entrée into the mobile world that is their future; and an alternative to delivery only via cable systems. The broadcasters would get a new ability to circumvent a blackout like the one that Time Warner Cable slapped on CBS in their fee fight last year.

Diller has said he will bail on Aereo if it loses at the Supreme Court. But that may be premature: Maybe the Big Four broadcasters can acquire Aereo themselves, owning most of it but letting it run itself. Then everyone, even viewers, would win.